Artist's Talk

Heaven and Earth

Reading Gilead through the Landscape of the Fox River

Joel Sheesley Oct. 2, 2017

I made this painting in 2006. [Holy, Holy, Holy, 2006] The title is “Holy, Holy, Holy.”We used to have this Transparent or Summer Apple tree in our backyard. It produced an extravagant show of blossoms each Spring followed by an overabundance of apples by midsummer – so much so that the tree split of its own weight. Had I been aware of where things were headed, I might have pruned it back and saved it. I sensed trouble brewing, but I was busy and distracted when the tree caved in. It collapsed under the weight of its apples after a summer rainstorm.

Holy, Holy, Holy, 2006

Holy, Holy, Holy, 2006

It was the extravagance of the blossoms that overwhelmed me. The tree was determined to show a bounty and I looked for a way to represent its lavish proliferation.The abundant blossoms conjured for me the image of the girl blowing bubbles, another kind of extravaganza, but one in which the effect is disproportionately more grand than the effort required to produce it. What I then would have called excess in both tree and girl, I now might also call grace – an extraordinary, unaccountable benevolence welling up for everyone.

I start with this painting because I believe that in Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, all of nature functions to buttress her narrative with this kind of grace. References to nature in Gilead are not extensive, but they regularly punctuate the text and establish a rhythm in the adagio-like pace of the story. John Ames intends to impart his “begats” to his son and so begins this long letter-novel in which Ames discloses his own story, that of his grandfather and father, and the emerging stories of his new wife and son.

The Ames paternal line (all preachers) is fraught with moral preoccupations beginning with the grandfather’s abstract abolitionism.The grand- father’s outraged moral eye drags across everything, touching the ground infrequently, and then only in violence. Otherwise his righteous passion burns within and knows no practical outlet other than to drive the man beyond the reach of family and congregation. John Ames’s father is left to question the anomaly of how his father’s indignant righteousness led him to an unrighteous and sketchy moral behavior. He frets over whether to leave buried or to exhume incriminating evidence of deeds that stemmed from his father’s judgmental moralism and bitter spirituality. Ultimately John Ames’s father simply leaves the territory; he abandons the prairie for country unstained by his father’s moral anger.

But earlier, in a pilgrimage to resolve the fallout of the grandfather’s idiosyncratic life, John Ames and his father set out to find the grandfather’s grave. Lost and trekking across the Kansas prairie they have a profound encounter with nature and are engulfed in its healing potential. [Moonrise Fox River, Nov. 12, 2016] They find themselves on that prairie as the sun sets and the moon is rising. Caught in the transfixing light of these two celestial bodies John Ames admits that he had never before,“given much thought to the nature of the horizon,” and Ames’s father says,“I would never have thought this place could be beautiful. I’m glad to know that.”

Moonrise Fox River, Nov. 12, 2016

Moonrise Fox River, Nov. 12, 2016

Discovery of beauty has turned on a light or opened a door. For Ames’s father, the light penetrates only so far, but Ames himself has lifted his eyes to the horizon and is initiated into a landscape that overwhelms the moral quests of his father and grandfather. In beauty he begins to nd a good that penetrates everything. This beauty is not an abstract ideal but landscape itself. At the end of Ames’s long letter he says,“I love the prairie! So often I have seen the dawn come and the light flood over the land and everything turn radiant at once, that word ‘good’ so profoundly affirmed in my soul that I am amazed I should be allowed to witness such a thing.”

Good and beauty are conjoined in the landscape, morality and grace come together, but John Ames does not reach that insight immediately. On the road to that realization, Ames confronts his own moral anxieties in the person of his namesake, Jack Boughton, whose return to Gilead after a 20 year hiatus thrusts Ames into anxious worry that Jack’s immoral behavior will once again infect Ames’s life and that of his wife and young son. This anxious worry becomes a continuous thread woven into much of John Ames’s long letter to his son.Ames finds himself sitting in judgment on Jack Boughton, but is prompted to question his own right to impose these judgments. It is witness of the natural world that routinely interrupts his judgmental stance.

But the natural world is never propositional in its witness. As Willa Cather once said, “the forests of the Ganges contain no sermons.” Landscape does not lend itself to exegesis. In Gilead, its meaning is rather absorbed sub-rationally and slowly over time, filling gaps in John Ames’s thinking until it presses into all his moral categories with its abundance and pardon. Ames observes that the sun has a feeling of weight in it, “pressing the damp out of the grass and pressing the smell of sour old sap out of the boards on the porch floor and burdening the trees a little as a late snow would do.” [Fox River at South End Park,West Dundee, September, 2016] In this way the witness of nature presses on John Ames and slowly forces from him the “sour sap” of his moral judgment on Jack Boughton.

Fox River at South End Park,West Dundee, September, 2016

Fox River at South End Park,West Dundee, September, 2016

The third major figure in John Ames’s long letter to his son is the boy’s mother, the wife that John Ames married late in life. She remains unnamed, called only “your mother,” and her story goes largely untold here, but her contemporary presence is constant as the letter unfolds. Ames describes her as an unlettered woman, essentially kind, and necessarily practical in her interactions with all aspects of life. She is a survivor of significant hardship and injustice yet when confronted with the opportunity for retribution, comments only, “It don’t matter.” We are given to understand that this pronouncement arises from a wide scope of experience that has led her to abdicate judgment on those who perpetrate wrong.

The boy’s mother is an outsider, someone raised almost out of the ground itself and in the company of a peripheral band of people never accepted in mainstream society. As such, in this story she too is something of a force of nature. Unlike her husband, she feels at ease with Jack Boughton though she knows that John Ames distrusts him. While Ames preaches he looks out and sees his son, wife, and Jack Boughton all sitting amicably together in their pew listening to his sermon. Ames wrestles with the witness of their friendship, a kind of prophetic plea against his skepticism of Jack.

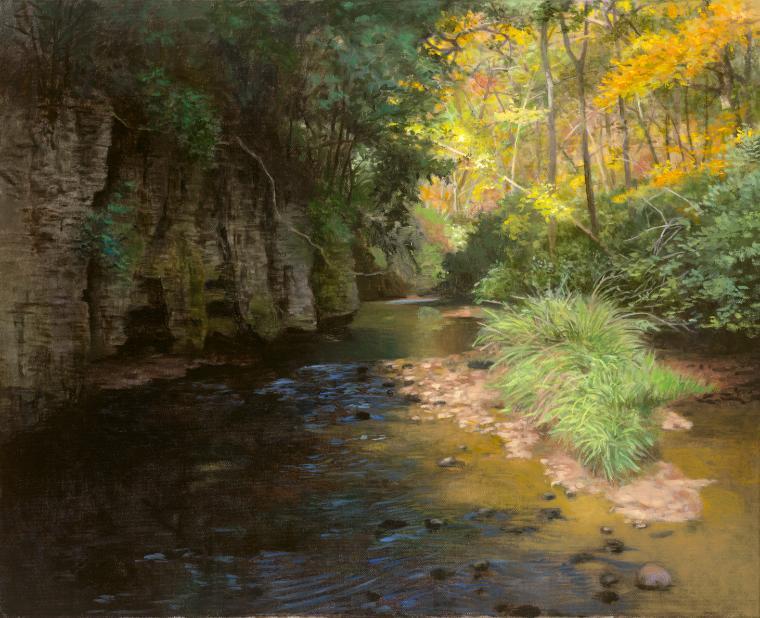

It is that skepticism that nature and the landscape constantly tend to assuage. Jack Boughton had a daughter born out of wedlock to a poor diffident girl whose family lived outside of town. Jack never acknowledged the child, excused himself of all responsibility for her, and offered not a penny of support for either child or mother. John Ames and Jack’s sister Glory go on a mission of mercy to visit the child and find mother and child playing in a stream. [Dolomitic Outcropping Mill Creek, Oct. 24, 2016] They throw water at each other and the child tries to help her mother build a small mud dam. Ames concludes his telling of the episode this way, “And the sun was shining as well as it could onto that shadowy river, a good part of the shine being caught in the trees. And the cicadas were chanting, and the willows were straggling their tresses in the water, and the cottonwood and the ash were making that late summer hush, that susurrus. After a while we went back to the car and came home. Glory said,‘I do not understand one thing in this world. Not one.’”

Dolomitic Outcropping Mill Creek, Oct. 24, 2016

Dolomitic Outcropping Mill Creek, Oct. 24, 2016

The child’s mother and family had consistently rejected the Ames’s and Boughtons’ benevolent and apologetic overtures, but this scene at the river also inveighs against Ames’s and Glory’s concept of recompense and mission of compassion. Their moral narrative has been rendered null by the shine on the water, the singing of the cicadas, and the willows’ straggling tresses. The moral agenda has not been eliminated by the landscape, but its parameters have been so widened that Glory has to confess that she simply does not understand them. Ames’s and Glory’s understanding of moral obligation will not be easily imposed on the picture they see there in the stream. The landscape will not confirm the limits of their moral agenda; it moves beyond such agendas.

The landscape reminds us that we “do not understand one thing in this world.” Landscapes do not point fingers or moralize, nor do they ever lie. Theirs is a silent witness. The ancient writer of the Psalms says of the skies, “they have no speech their words are not heard.” This world, in spite of our most intelligent speculation, is essentially a mute mystery to us. We interfere with its purpose, drain its wetlands, pave its meadows, and strip mine its minerals, yet the landscape and its terrific absorptive power abide. It quietly holds within all the curse of humanity. “Cursed is the ground,” Genesis reminds us, “because of you.” Yet embracing whatever pain, the landscape exudes a generous spirit.

Like a biblical prophet we may want the fields to “cry out.” [Fox Glove in Bloom Dayton Bluffs, June 6, 2017] But brought low as the fields may be by human avarice, the landscape remains mute and meekly absorbs the excesses of human imagination. So Jack Boughton’s disgraceful and arrogant disregard for his own child is absorbed, as are all of human history’s acts of greed. This is the morality that slowly emerges in John Ames’s long letter. It is layered as land, in which archeologists show us human history itself as layered. Scripture asserts that human beings were drawn, molded, formed from the ground. Our return to it is a justice mixed with grace. Banished from the garden in life, the ground receives, takes us back, in death.

In Gilead, landscape grace comes to light under the perpetually shining sun. [Ferson Creek Sunrise, Oct. 13, 2016] Its constancy as the earth turns awakens the connection between heaven and earth. Out on the Kansas prairie, it was in search of Ames’ grandfather’s grave that Ames and his father became aware of the great lights in the heavens. Later, enthralled with an Iowa sunrise, John Ames reflects on the interaction of earth and sky. He observes that, “Light is constant, we just turn over in it. So everyday is in fact the selfsame evening and morning. My grandfather’s grave turned into the light, and the dew on his weedy little mortality patch was glorious.”

Ferson Creek Sunrise, Oct. 13, 2016

Ferson Creek Sunrise, Oct. 13, 2016

Glory is a word we scarcely understand, yet it is pressing on us from every direction. This is what we learn from the Sanctus:“Holy, holy, holy, Lord. God of power and might. Heaven and earth are full of your glory.” Like the constancy of the light of the sun, the glory that fills the earth is something that we daily “turn over in,” and so realize as if it is something new every day. As in the Lamentations of Israel, we sense that the faithful compassion of God is new every morning. But this glory is within the elements of the creation itself; it abides and supports any daily discovery and celebration that we might make of it. Glory is not a derivative, not a byproduct. John Ames finds this confirmed by the atheist Ludwig Feuerbach who says of water that it “has a significance in itself, as water; it is on account of its natural quality that it is consecrated and selected as the vehicle of the Holy Spirit.”

[Glory, 2006] I made this painting in 2006. It had no title until well after it was made. This means that the making of the painting was an open-ended search, an exploration or discovery-based project. It only received the title “Glory” upon completion. We discover things like glory. We do not presume to know them ahead of time. We do not set out to illustrate them. The glory of the dew on Ames’ grandfather’s “weedy little mortality patch” came into view as the earth rolled to the East and was illuminated by the constant sun. So glory found a kind of containment in the grounds of a cemetery, as in this painting it shines out from a puddle in the road.

Glory, 2006

Glory, 2006

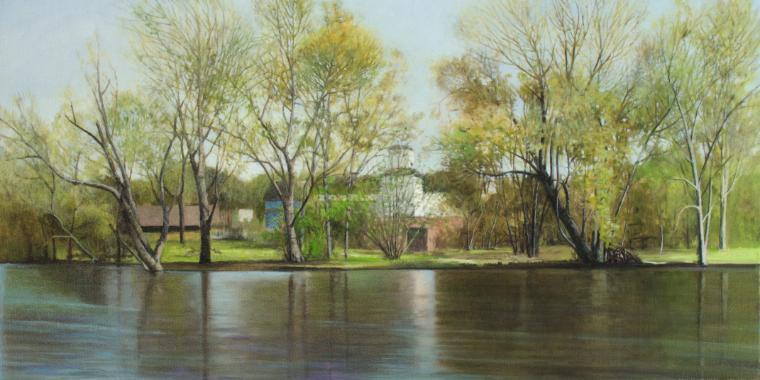

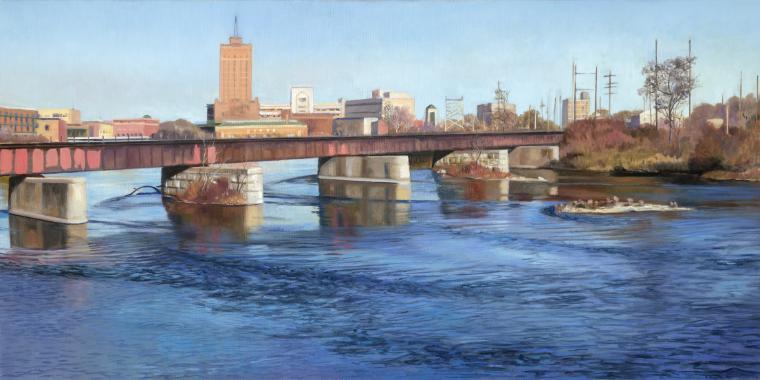

In Gilead, this glory never dissolves into an uninhabited wilderness. The prairie is an inhabited realm. [Oswego Grain Elevator on the Fox,April 17, 2017] At times the prairie comes back into cultivated fields and orchards as it did around Ames’ old church. The town of Gilead with its water tower and grain elevator may go to weeds, but glory resides where human habitation may take account of it. There is a kind of hope in such a place. A hope Ames says that “the place was meant to encourage, that a harmless life could be lived here unmolested.” Even though the place alone can never fulfill this hope, it protects and nourishes it as a kind of longing. Midwestern towns were meant to shelter such hope. [Fox River, Island Park Geneva, Sept. 2, 2016] Ames says, “To play catch of an evening, to smell the river, to hear the train pass. These little towns were once the bold ramparts meant to shelter just such peace.” At the close of the book Ames remarks, “This whole town does look like whatever hope becomes after it begins to weary a little, then weary a little more. But hope deferred is still hope.” [North Ave. Bridge,Aurora Nov. 29, 2016]

Oswego Grain Elevator on the Fox, April 17, 2017

Oswego Grain Elevator on the Fox, April 17, 2017

Fox River, Island Park Geneva, Sept. 2, 2016

Fox River, Island Park Geneva, Sept. 2, 2016

North Ave. Bridge,Aurora Nov. 29, 2016

North Ave. Bridge,Aurora Nov. 29, 2016

Landscape, as interpreted by St. Paul in his letter to the Romans, is entirely enmeshed in hope deferred. [Jan. 2 Lippold Park Sunset, 2017] He says, “the creation was subjected to frustration ... in hope that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the glorious freedom of the children of God.” Somehow down the line, St. Paul says, the children of God and the landscape will share in freedom and glory.

Jan. 2 Lippold Park Sunset, 2017

Jan. 2 Lippold Park Sunset, 2017

But how can they share it? How does the judgmental nature of John Ames’ and his ancestry’s righteous moral preoccupation mesh and share anything with the suffering landscape that, unlike human suffering, is not a consequence of choice but of a curse imputed by we humans ourselves?

I ask this question and find myself turning to the Christ-like character of the landscape. St. Paul interprets the landscape as a revelation of God’s divine nature. The landscape, he says, leaves us without excuse for our sin because in it what may be known about God is plain to see. The landscape is original blessing, but it also prefigures Christ’s sacrifice. On it our sins have been pinned. Again we are reminded, “Cursed is the ground, because of you.” Like Christ the creation was subjected to frustration,“not by its own choice.” This is in parallel with Jesus who in Gethsemane had said, “Not my will, but thine be done.” Through Christ’s sacrifice we have forgiveness of sins. If the landscape foreshadows Christ’s sacrifice, it may be proper to expect that it also participates in our reconciliation. What form that takes remains mysterious and lies somewhere in the realm of the resurrection.

Looking to the resurrection, both Jesus and St. Paul used nature metaphors to imagine it. In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul invoked the bodily characteristics of a variety of plants and animals, as well as astronomical bodies, to help his readers conjure what the resurrected realm might be. We can take it from this writing that the resurrection includes the natural world and therefore a reconciliation between humans and nature is part of it. In the Gospels, this reconciliation or salvation is not a distant but rather an immanent reality. So the liberation of nature may also be considered concurrent with our own “already and not yet” salvation. As such it is not improbable that nature and humankind already share a work together toward the day of resurrection. Perhaps it is in this partnership that landscape plays its part in easing John Ames’ anxious judgmental predispositions and brings him to reconciliation with Jack Boughton.

Partnership with the landscape develops when we confront landscape as responsive and vital – when we confront it, in Robinson’s terms, as freshly turning over in the light of the sun. Landscapes do not fulfill our expectations, they lead us instead to long for something beyond expectations, an awareness of an ever larger world, something more and other just out of sight. In landscape we discover a kind of homesickness and we conjure a sense that our belonging lies elsewhere – we become lost in a palpable absence. If a landscape artist sets out to define, clarify, or fulfill that absence, if she aims to show us precisely what we were looking for, she turns the landscape into a melodrama.

The more serious artistic quest is to devise a view of the landscape that like the land itself leaves the longed-for subject in disguise, in a camouflage that makes presence and absence hinge on one another. [Sycamore on Big Rock Creek, 2017] Beauty, said the 19th C American landscape artist George Inness, “depends upon the unseen.” Just so, the subject of every landscape metaphor is “unseen,” disguised within the land so we might know it more fully than we would had it been given to us as an abstraction. “The intellect desires to de ne everything,” wrote George Inness, “but God is always hidden and beauty depends on the unseen, the visible upon the invisible.”

Sycamore on Big Rock Creek, 2017

Sycamore on Big Rock Creek, 2017

This is what Marilynne Robinson accomplishes in Gilead. Her landscape partners with John Ames toward his slow emancipation from the judgmental moralism that haunts his ancestry. Ames is a theological man. His entire life has been a theater in which Christianity as a settled system of beliefs has been weighed and critiqued. But John Ames’ older brother Edward functions in the book to show us how faith as no more than a settled system of beliefs defined in purely intellectual and propositional terms is a weightless and empty abstraction. Throughout the book Ames confronts the limits of religion as mere intellectual assent. Sitting in the empty church at the point of his reconciliation with Jack Boughton, Ames says, “When this old sanctuary is full of silence and prayer, every book Karl Barth ever will write would not be a feather in the scales against it from the point of view of profundity...”

[Bluff Spring Fen, Oct. 31, 2016] Again and again John Ames locates profundity in realms that are beyond exegesis. He finds it in landscape, in ordinary people and their interrelationships, and in the stories that biblical texts represent. As Ames muses upon the story of Hagar and Ishmael he wanders in his mind into the wilderness landscape into which they were driven and writes, “Even that wilderness, the very habitation of jackals, is the Lord’s.” A few lines later in his letter Ames muses again on the moon. He writes, “The moon looks wonderful in this warm evening light, just as a candle flame looks beautiful in the light of the morning. Light within light. It seems like a metaphor for something.” He goes on, “It seems to me to be a metaphor for the human soul, the singular light within the great general light of existence. Or it seems like poetry within language. Perhaps wisdom within experience. Or marriage within friendship and love.” Ames continues, “I believe I see a place for it in my thoughts on Hagar and Ishmael. Their time in the wilderness seems like a specific moment of divine Providence within the whole providential regime of Creation.”

Bluff Spring Fen, Oct. 31, 2016

Bluff Spring Fen, Oct. 31, 2016

Providence within the providential regime of Creation. Landscapes, these bounded glimpses of nature, even of wilderness, propose the frontiers of our encounter with God. They are the language within which poetry emerges, the experience in which we find wisdom, the friendship in which we celebrate marriage. We are geographical beings and we locate ourselves within the spreading ecology of the landscape: our “soul, the singular light within the great general light of existence.” In our encounter with landscape we are lifted away from any conception that a merely intellectual construction, a theology understood merely as a settled system of beliefs, can ever adequately define and limit the extent of God’s grace in the world. Instead we are put in a place where human judgment must always be deferred. St. Paul in his letter to the Romans begged his readers to realize that judgments on others only become judgments of ourselves and show us to be the ones who are disdainful of “the riches of [God’s] kindness, tolerance and patience.”

The landscape is a full revelation of those riches. It was in creation, in “that which has been made,” that St. Paul saw God’s divine nature revealed. John Ames also discovers divine grace in the landscape and it is in concert with the Iowa landscape that he comes to reconciliation with Jack Boughton. In partnership with that landscape John Ames also discovers these riches in the story of his own life. Indeed Gilead is a revelation of the riches of God’s kindness, tolerance and patience celebrated in the life of John Ames. [Holy Holy Holy, 2006] We return then to the Sanctus,“Holy, holy, holy. God of power and might. Heaven and earth are full of your glory.”

Holy, Holy, Holy, 2006

To download a PDF copy of this talk, please follow the link. Joel Sheesley Artist Talk