Learning to Show Up Fully

A History of Wheaton College’s Asian American Pacific Islander Community

Words: Liuan Chen Huska ’09

Photos: Courtesy of Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections

1946 Tower Yearbook Photo of the Chinese Fellowship. Row 1 (L-R): Madeleine Young ’50, Emma Loo, Mildred Young ’47, L. Wang, Chun, Tam. Row 2 (L-R): Choy, Wong, Chang.

Names are taken directly from the Tower Yearbook caption.

In September 2023, when Wheaton College’s Historical Review Task Force released its report on campus race relations spanning 1860–2000, the report focused mainly on the experiences of black students. Yet Wheaton’s annual enrollment of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders has grown from just one or two students after World War I to almost 250 in 2023. These numbers make AAPI students the largest racial minority group on campus.

Following the report’s release, some AAPI students were disappointed they did not see their own experiences reflected in the report, according to Task Force Co-Chair Katherine Graber M.A. ’12, M.A. ’20.

Office of Multicultural Development Director Dr. David Cho M.A. ’19 and his team were ready for student responses. They hosted a series of “Restoration Stations” that met multiple times a week for the first few weeks to walk through the report together. They intended to follow Scripture’s model to handle the pain of the past—through remembrance, commemoration, and community presence. “You remember. You write down the things that have gone well and not gone well,” Cho said. “You continue to plow together, grow seeds, water them, plant more. You continue to process.”

Wheaton’s AAPI Students Over the Decades

After World War I, one or two AAPI students enrolled at Wheaton in any given year, based on yearbooks, newspapers, and sparse archival records. History and geography contributed to the minuscule AAPI campus population.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act banned all Chinese laborers from entering the country. In the informal 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement, the Japanese government agreed to keep Japanese laborers from immigrating to the U.S. in exchange for San Francisco allowing Japanese students to integrate with white students in schools. Finally, the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act banned almost all Asian immigrants. Those who were already present tended to stay on both coasts. The HRTF report describes Wheaton College in 1930 as “an almost all-white institution in an almost all-white town in an almost all-white county.”

A report from the Christian Beacon, a national paper founded by Carl McIntire, gives a tiny glimpse into one Asian American student’s experience at Wheaton during that period. Dated February 20, 1936, the newspaper covered a campus revival, including parts of a student’s letter home. “Among the first to speak was a Japanese boy who told the students he was ashamed of the Christian atmosphere in Wheaton, there were actually animosities against him because of his race,” the student wrote, “Oh, what convictions there were that day.”

When World War II started, the College agreed to accept Japanese American students who would otherwise have gone to internment camps. AAPI enrollment in 1944 jumped to 22. Esther Lee Cruz ’06, an HRTF alumni member, finds this period of Wheaton campus life fascinating. During the height of the war with Japan, “We let in a lot of Japanese students on purpose, not by accident,” she said. “That’s a decision somebody needed to make at a time when people were actively racist.”

In 1965, the U.S. passed the Hart-Celler Immigration Act, legislation that lifted restrictive quotas against Asian immigrants. The decade also saw a growing civil rights movement and calls for racial justice, spurring Wheaton’s own policies to recruit more Black and Latino students. In the late 1980s, the College began hosting missions conferences for Korean ministry leaders, leading to increasing enrollment of Korean students. Wheaton’s AAPI student population continued to grow, from just over ten new AAPI students per year in 1975 to around 120 new students per year in the 1990s.

From Hiddenness to Transparency

When Jeanette Lowe Hsieh M.A. ’66 entered the Wheaton College Graduate School to study Christian education in 1964, she kept aspects of her identity hidden. She didn’t reveal that her parents were immigrants or spoke English as a second language. She didn’t eat Chinese food or with chopsticks. “I needed to be as Anglo as possible,” Hsieh said. “In my writing and in my stories and in my work, I didn’t include anything that would give a hint that I was an Asian American woman.”

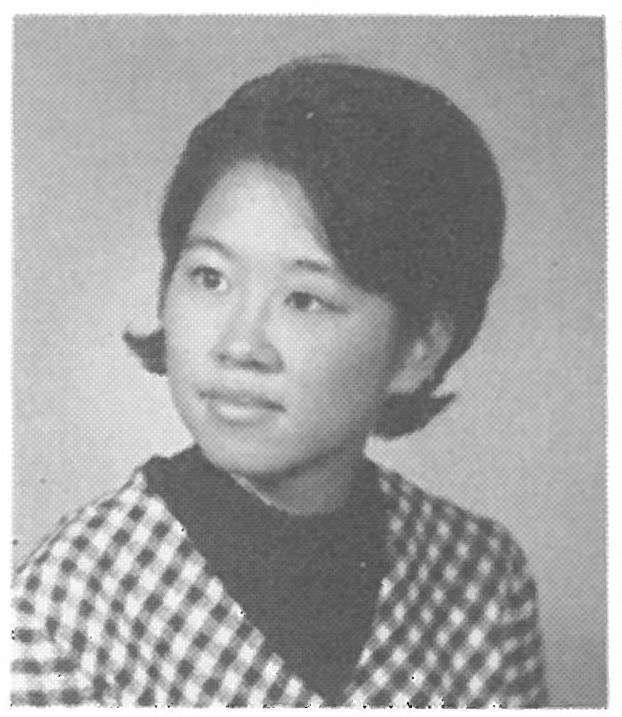

Jeanette Lowe Hsieh M.A. ’66

Hsieh was trying to answer a question that had plagued her from the moment she stepped foot on Wheaton’s campus from Southern California, where she grew up: “Am I good enough?”

From Hsieh’s perspective, Wheaton’s student culture often tends toward perfectionism, a tendency she absorbed as a student. On top of that, Wheaton’s faculty was also almost all white and male at the time. Her efforts to prove her worth—both in striving toward perfection and in conforming to the majority campus culture—came at the cost of showing up fully.

Hsieh returned to teach in Wheaton’s education department from 1990–1997, serving as chair of the department in the latter ’90s. One year, she led a discussion for the Nurturing Bicultural Identity conference on campus. For the first time, she felt she could be transparent about being Asian.

“It was a mid-career identity transformation for me,” she said. “Up to that point, I had negotiated everything in my professional career from the perspective of majority culture. I was fearful of rejection and failure.” Leading that group was the beginning of a new realization: “I should be able to celebrate who I am as God’s creation as an Asian woman.”

Nurturing Asian American Pacific Islander Identity

Like Hsieh, other AAPI students, faculty, and staff through the years have found ways to affirm their ethnic identity within a majority-white campus culture. A Chinese Fellowship existed on campus as early as 1944. In the early 1970s sociology professor Ka Tong Gaw gathered AAPI students together for a series of conversations on race. Craig Nakatsuka ’75 joined in.

Growing up in racially diverse Hawaii, Nakatsuka came to Wheaton relatively innocent about Asian American struggles on the mainland. “Professor Gaw wanted us to be aware that we don’t necessarily have to have the Asian cultural mentality of politeness, fitting in, and conforming,” Nakatsuka said. “Discrimination is there and should be called out.”

When Jon Ro ’89 came to campus a decade later, he connected with suitemates and joined the Men’s Glee Club. Although he formed meaningful friendships, he often felt like an outsider as an Asian and a missionary kid. At times, this made it difficult for him to muster the energy to bridge the social gaps. In 1986, Ro, his brother David Ro ’89, Gordon Ott ’88, and Paul Suzuki ’88 started the Asian Friday Night Fellowship, which later became Koinonia. With Professor of Mathematics (now emeritus) Dr. Paul Isihara as their faculty adviser, Ro and his peers formed a safe space where they could fully be themselves.

The Office of Minority Affairs began in 1988 and hosted events celebrating AAPI heritage. The office also sponsored creative publications, including “Enter the Heart” in 1997 and “Not Everything is Black and White” in 1999.

“Brace yourselves because it’s simple—we are here,” wrote Patty Keyuranggul ’98, M.A. ’03, in the 1997 publication. “We want to be part of the community, we are part of the community, and our personal histories are what we come with.” Keyuranggul and others go on to share these histories, from grandparents who left China during World War II, to being called a banana—yellow on the outside and white on the inside.

Forging a space of shared belonging for Asian, South Asian, and Pacific Islander Americans hasn’t always come naturally. Histories of animosity between various Asian countries have sometimes bled over into interactions between AAPI students, not to mention different ways of worshiping, eating, and communicating. When Donghyuk Lee ’23 came to campus as a Korean American who grew up in the Philippines, he noticed that international students from Asian countries didn’t hang out with Asian American students. They were often not as aware of or invested in campus conversations around race.

Lee joined the Historical Review Task Force midway through the process as a student representative. “Knowing the institution’s history made me better understand why things were the way they were,” Lee said. “I see the progression line.” Lee’s involvement also made him aware that the commitment to kingdom diversity cannot be carried by students alone. “Even the students who are most passionate about diversity are going to be gone in four years,” Lee said. “The College has to work on it even when students don’t care.”

At the OMD, Cho and others have been working to bridge the gaps between AAPI ethnic groups, among racial minority groups, and with the wider campus. At Koinonia and OMD gatherings, Cho often shares from 1 Corinthians 12. “How many bodies are here?” he begins. Students will volunteer a number like 40 or 50. Cho replies, “Just one.”

Agents of Hope

David Iha ’62 returned to campus for his 60th reunion in 2022. Iha’s father immigrated to Hawaii from Okinawa right before the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement banned Japanese laborers. His mother immigrated in 1919 amid the Spanish flu pandemic, a few years before the 1924 law that banned all Asian immigration. Iha’s parents didn’t attend high school. They labored on a sugar plantation, where Iha watched his older brothers organize workers for the union.

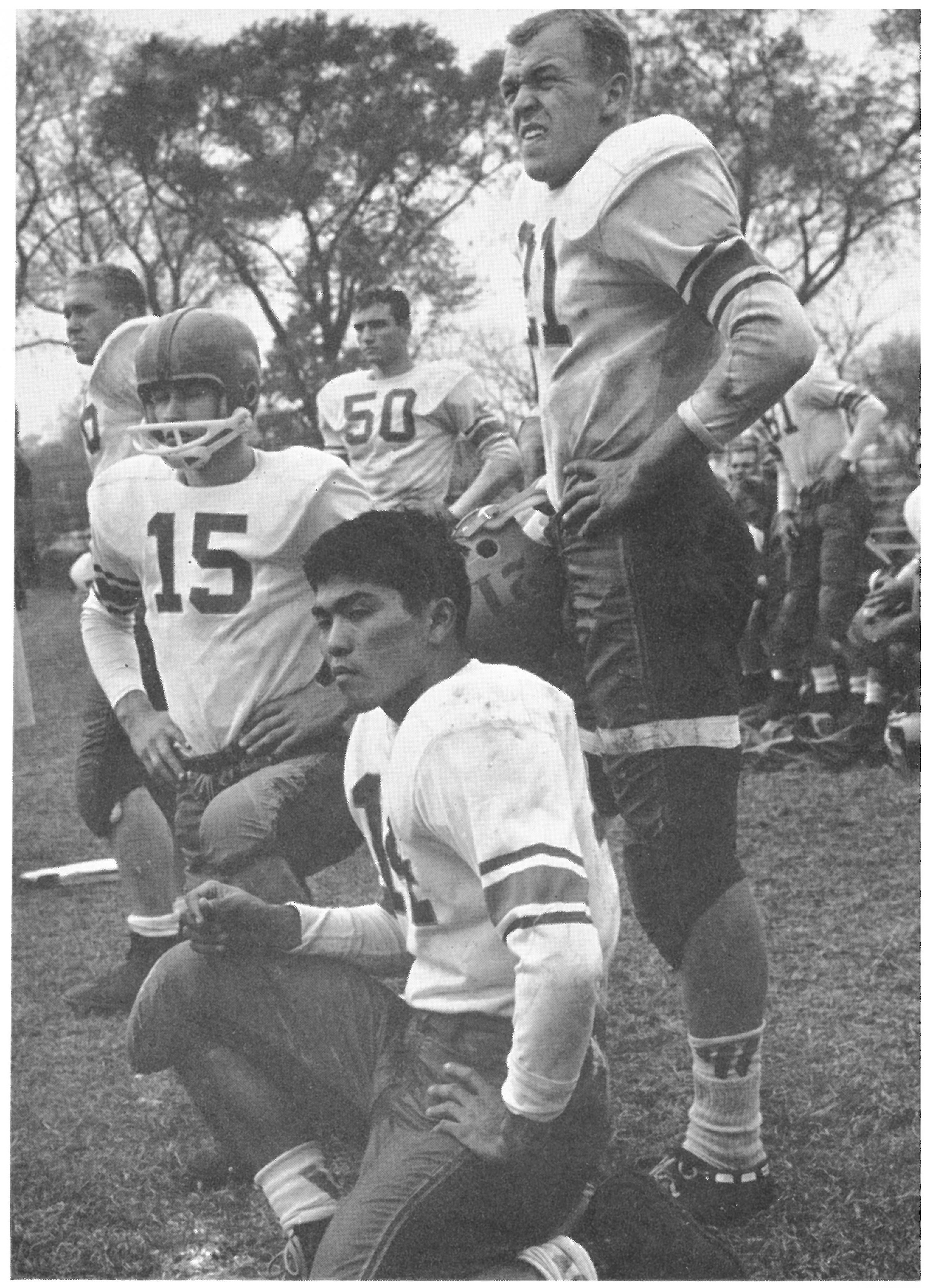

David Iha (kneeling), 1961

Iha didn’t experience overt racism until his time at Wheaton took him off campus. On a tennis trip down south one spring break, Iha debated on whether to use the colored or white bathroom. On another ROTC trip to Fort Benning (now Fort Moore), Georgia, he started walking to the back of the bus and the driver said, “You can get up front.” Iha replied, “No, I’ll stay in the back.”

Iha was named Wheaton’s MVP in 1961 and inducted to the Athletics Hall of Honor in 1991, for his contributions to the football and tennis teams. “I’m amazed at how many Asians there are now,” Iha said of his recent visits to campus. “Wheaton has made tremendous progress in terms of diversifying its student population.”

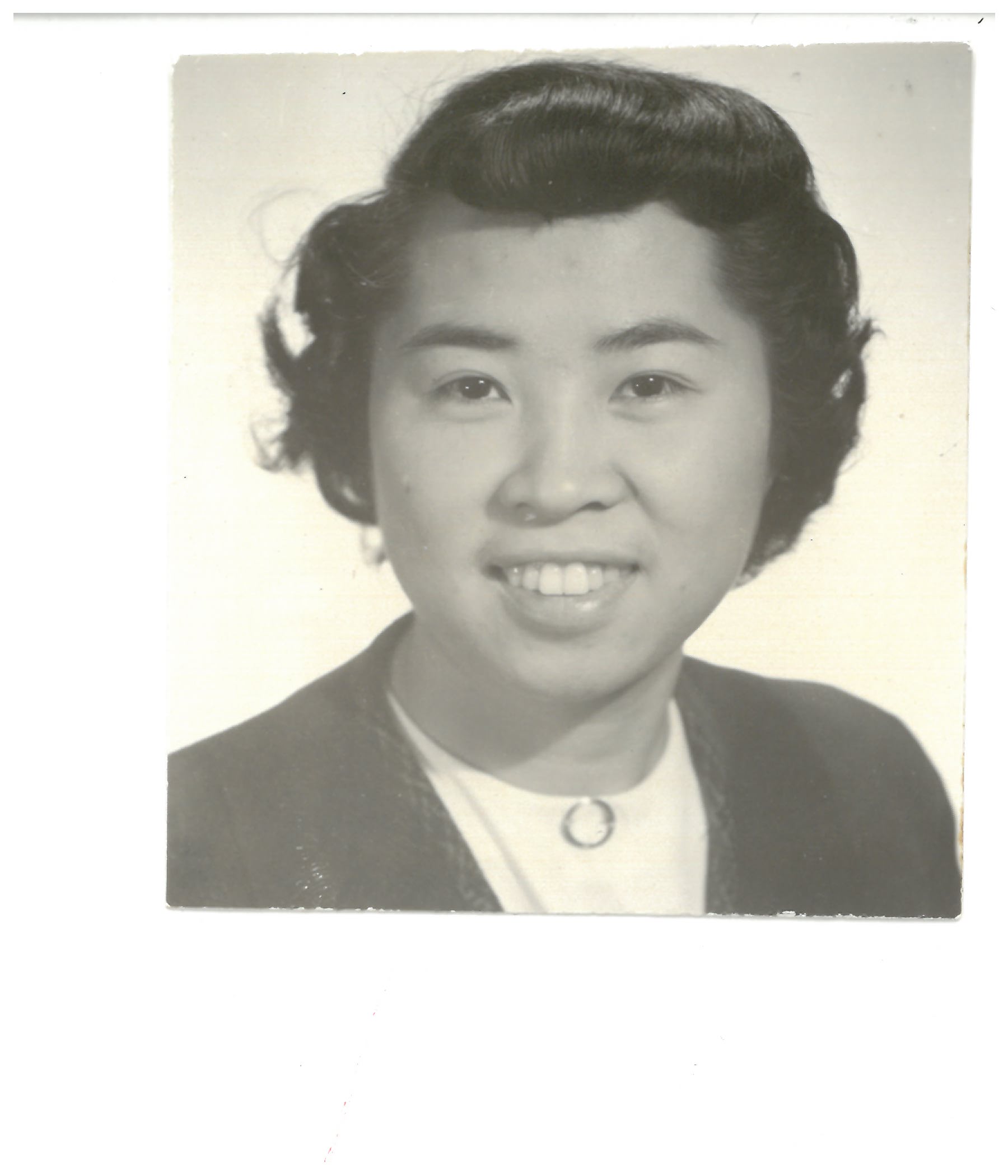

Trustee Dale Wong ’85 has a family legacy woven into Wheaton’s AAPI history. His parents, Hoover Wong ’52 and Madeline Young ’50, were among 13 family members who attended the College. His aunt, Mildred Young ’47, taught Greek in the early 1950s and is Wheaton’s first identified faculty person of color. Wong co-chaired the HRTF and is interested to see how the task force recommendations will impact the experiences of faculty, staff, and students of color. “President Ryken, the Senior Administrative Cabinet, and the Board are very intentional and serious about trying to make Wheaton a place where every student, every staff and faculty member, regardless of ethnicity, can really call Wheaton their home,” said Wong. He added that for some, changes will come too fast. For others, they won’t come soon enough.

Regardless of pace, all agree that there is work ahead. “Asian Americans—men and women—can play a significant role in serving the kingdom at Wheaton,” said Hsieh. “There may need to be a focused effort in celebrating and cherishing Asian American contributions.”

Mildred Young ’47

For Lee Cruz, the work is tied to our Christian calling. “God’s call is to love outsiders,” she said. “The church can be a thermostat, setting the tone, rather than a thermometer reflecting broader society, when it comes to how we treat them.”

Since Cho began his role directing the OMD, he has helped develop an Asian American studies minor within the sociology department, as well as sharpen other American ethnic studies programs. “I don’t see them solely as identity issues,” Cho said. “They are related to history, sociology, psychology, art, music. They can be integrated through Scripture and faith . . . through any angle we see.”

Cho points to other possibilities for commemorating Wheaton’s AAPI legacy—such as endowed lectures, scholarships, and positions and naming buildings after notable AAPI community members. “We can create anchor points,” Cho said, “not to get stuck in the past, but as part of the process of knowing, understanding, and being able to share.”

Today, Wheaton’s AAPI faculty, staff, and students continue to carve out a place for themselves, building on the efforts of those who came before. Provost Karen An-hwei Lee finds symbolic meaning in the image of a footstool, which she uses to stand at the podium in Edman Chapel as a petite Asian American woman. “The footstool is not only an object of function and utility, but also a symbol of how a person’s role and position can be used as a resource to empower others,” Lee said. She was delighted when her colleague, Humanitarian Disaster Institute Program Administrator Joy Lee M.A. ’22, asked to use the footstool too to speak during Koinonia Chapel this year. “In a way, through our shared global heritage and Christian faith, we share a common platform.”

Lee also draws from the gospel-centered wisdom of African American spiritual traditions. Similarly, she views Asian American churches as agents of hope, channeling God’s restorative work through generational healing of historical trauma. “If one of us is harmed or despised, the whole body is wounded,” Lee said. “In our shared humanity, we have a collective opportunity to bear witness to God’s redemptive work through Jesus Christ and to praise God for his gift of salvation for all.”