Recapturing the “Art of Attention”

Wheaton professors Dr. Taylor Worley and Dr. Nate Thom received a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust to conduct research at the Art Institute of Chicago on the impact of art on brain health and development.

Words: Grant Dutro ’25

Photos: Courtesy of the Wheaton College Summer Institute

Students wander through contemporary exhibits at the Art Institute of Chicago.

A rising senior in high school walked into the Art Institute of Chicago with a large group of fellow study participants. Outfitted with a chest strap and a watch to measure her heart rate, she was asked to stroll the gallery, observe the works of art, and mark down her thoughts in a little booklet. Despite what some general audiences may associate with museums, she was not asked to ponder idyllic landscapes or intricately patterned tapestries. Instead, she was directed to a contemporary exhibit—prompted to engage a sculpture of a sink and a giant pile of candy next to the gallery wall.

This past summer, approximately 60 people participated in the experimental “Art of Attention” study conducted by Associate Professor of Biology Dr. Nate Thom and Visiting Associate Professor of Art History Dr. Taylor Worley, funded by the Templeton Religion Trust. In this ongoing research, Thom and Worley pose a question of aesthetics: How does viewing and contemplating “difficult art” affect and grow its audience psychologically, physiologically, emotionally, and spiritually?

The two professors share a mutual interest in what develops a healthy brain. Thom has studied neuroscience extensively, once even working with members of the U.S. military to discern whether contemplative practices created better performance in the field. Similarly, Worley explores ways to encourage people to think differently than they normally would, particularly in how art cultivates healthier mindsets. These overlapping interests brought the two Wheaton professors together for a unique, liberal arts collaboration.

Thom and Worley related that their study is part of a larger discussion of art’s cultural importance.

“Museums are very interested in these sorts of questions, especially post-pandemic,” said Worley. “They are trying to argue for their value in society and culture, so you see these ‘mindful art’ programs all over the place.”

According to Thom and Worley, there is also a growing push in the sciences to ask questions concerning the origins and implications of artistic preferences, a developing subject called “empirical aesthetics.” Within this movement, Thom and Worley advocate for the importance of conceptual art: Unlike the typical “pretty pictures” that many people associate with artistic pursuits, conceptual art holds a very different purpose.

“Most people studying empirical aesthetics have been looking at art from the perspective of ‘Is it pretty or beautiful?’ and what kind of experience that can translate to,” said Thom. “Conceptual art has a completely different goal. The goal is to make you go ‘Wait, what?’ And that is moderately stressful.”

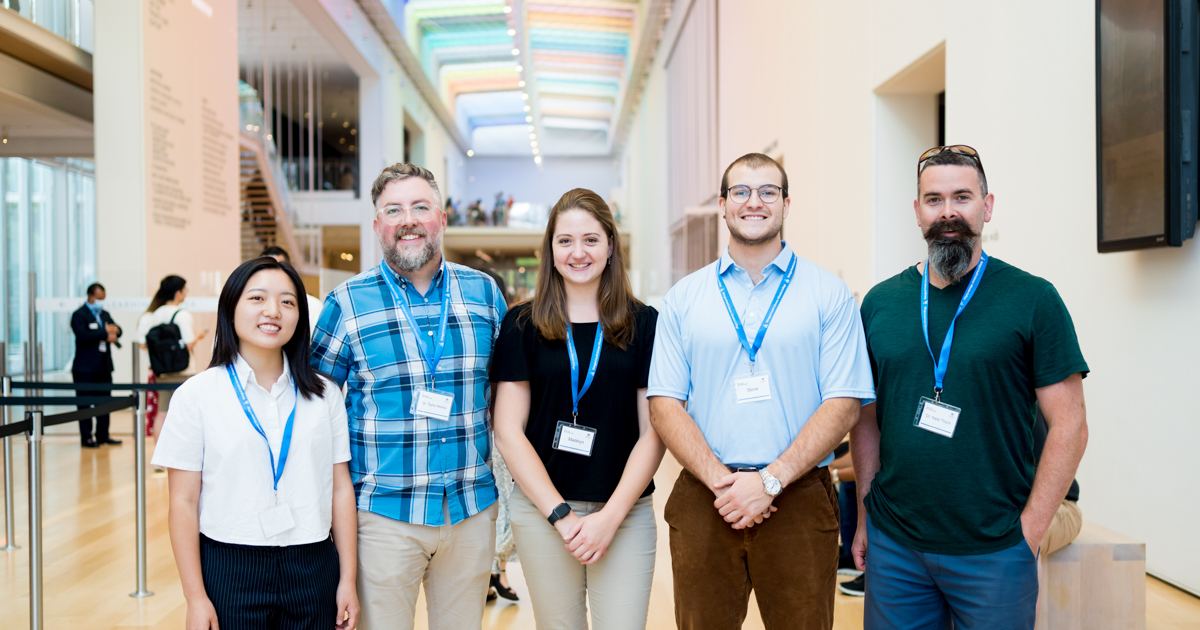

Dr. Taylor Worley (second from left) and Dr. Nate Thom (far right) with undergraduate student research assistants at the Art Institute of Chicago.

To Thom and Worley, the challenging aspects of conceptual art are a response to the current media environment of society at large.

“How do we make art more distinct than the info-tainment, the onslaught of technology, and living self-curated lives?” Worley asked, concerning the question conceptual artists face. “We are then able to think about conceptual artwork not merely as cultural artifacts but as tools for affecting people in dramatic ways.”

For their study, Thom and Worley assembled a large group of willing participants, many of whom were students in Wheaton College’s Summer Institute (a premier pre-college program) with parent or guardian approval. The group consisted of experts, people with extensive familiarity with art, and nonexperts completely fresh to the museum experience. Thom and Worley then brought the group to the contemporary art galleries where participants were tasked with a ‘slow looking’ exercise with up to five works of art. Thom and Worley hypothesized that viewing conceptual art would generate measurable patterns in heart rate variability. To test this, they equipped each participant with Polar H-10 chest straps and Polar watches to measure heart-rate variability.

Research study participants engage in “slow looking” and take notes in booklets.

Thom and Worley also gave participants a booklet containing information about the pieces and instructions to engage in “slow looking.” The booklet’s text described how the average art museum visitor spends an average of eight seconds with each work they encounter. “Slow looking” asks the viewer to engage with the art for longer periods of time, to “allow yourself to make your own discoveries and form a personal connection with it.” After observing each piece for around five minutes, participants rated their experience with the conceptual art.

The “Art of Attention” project reflects a uniquely Wheaton opportunity to synthesize humanities and STEM studies. Wheaton’s commitment to liberal arts enables professors to collaborate across disciplines—something that is not prevalent at other types of academic institutions.

“I studied at big institutions all the way through my education, and collaboration for me at those places would be me talking to another cognitive neuroscientist that does slightly different work,” said Thom. “People like me and Dr. Worley would never be on the same end of campus.”

Thom adds that Wheaton creates space for faculty and students to work in a variety of disciplines, such as combining artistic contemplation with scientific study.

“How can we bring in our understanding of contemplation and knowing God, without being overly reductive, and measure that experience physiologically and psychologically?” said Thom. “Most people would not want to spend their time answering that. But here, because of the environment, it makes sense.”

Thom and Worley agreed that the project requires a high level of mutual learning and trust between each other.

“For both of us, it has been like learning a foreign language,” said Thom. “Most people in our season who have spent years learning their language really do not want to learn another one.”

“Dr. Thom has to trust me and I have to trust him,” said Worley. “It has been a real learning process. But what has happened in the context of collegiality and trust is that we come together in our bigger aims.”

The two professors are in the process of analyzing the outcomes and other data from their summer study at the Art Institute. As of now, the heart-rate variability data and written reflections look promising. After analysis and interpretation, the two will prepare a journal article or a conference presentation. Since the project is a pilot, they hope that the experiment’s results will elicit enough positive feedback to allow them to explore further ideas.

“There is a hopeful horizon of how this might contribute to a more humane and charitable world where we train ourselves to slow down and listen to a text or cultural artifact,” said Worley. “Those practices are habituating in us an inclination toward humility, patience, and charity.”

Student participates in the “Art of Attention” study.