Prewriting and Outline

Prewriting

Every author fears that dreadful paralysis in front of a blank computer screen or a stark, white sheet of paper. “What do I write?” “How do I express my scattered thoughts?” “How do I overcome my fear of this assignment?!”

Whether one is writing a narrative, persuasive argument, research essay, or almost anything else, prewriting is a vital part of the writing process. It is a helpful tool for stimulating thoughts, choosing a topic, and organizing ideas. It can help get ideas out of the writer’s head and onto paper, which is the first step in making the ideas understandable through writing. Writers may choose from a variety of prewriting techniques, including brainstorming, clustering, and freewriting.

Brainstorming

In thinking about the assignment, write down whatever thoughts enter your mind, no matter how strange or irrelevant they may seem. For example, if your assignment is to write an informative research paper on AIDS in Africa, you might write down anything that comes to mind about AIDS in Africa: STDs, few doctors, limited medicine, prostitution, despair, orphans, grandparents as guardians, need for physical and moral education, etc. Once on paper, you can use these phrases to help formulate your ideas and sentences.

Clustering

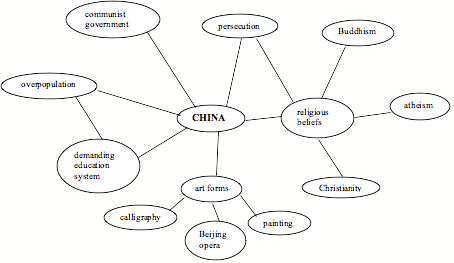

Begin with a word, circle it, and draw lines from the circle to other ideas as they occur to you. You may circle these new ideas and look for relationships between the various ideas, connecting them with lines. The movement here is from a general topic (in the center circle) to specific aspects of that topic (in the off-shooting circles).

Freewriting

Set a time limit (ten to fifteen minutes is suggested) and write in complete sentences as quickly as possible. Do not pause for correction or wait for a deep thought. If nothing comes to mind, write, “Nothing comes to mind,” until a new thought strikes you. The purpose is to focus and generate material while postponing criticism and editing for later. Journal writing and rough drafts are often a form of freewriting.

No matter which method of prewriting you choose, the key to success is turning off the internal editor or critic within yourself and working as swiftly and freely as possible. Most writers have an inner critic which assesses their writing as they compose. Although this critic is valuable in rewriting a paper, its judgmental character hinders thought flow in the initial stages of writing. The best way to prewrite is to ignore the voice of your inner critic and to write fluidly without stopping to correct mistakes. Later, when you look at what you have written, you can begin to re-organize what you have written; crafting your paper into points that are clear, concise, and relevant.

Outline

Constructing an outline is one of the best organizational techniques in preparing to write a paper. In making a basic outline, begin with a thesis and decide on the major points of the paper. Under these major points list specific subpoints. According to section 1.8 in the MLA Handbook, the descending parts of an outline are normally labeled in the following order: I., A., 1., a., (1), (a). Remember that if an outline includes a I., logic requires that it include a II. If there is an A., then there needs to be a B. (This rule assures that there are no unnecessary categories in the outline—in other words, it forces the writer to keep his/her thoughts specific and in order.)

Thesis: Saga deserves a #1 rating in The Princeton Review.

I. There is a wide variety of food.

A. Pizza

1. Saga is always creating new types of pizza.

a. Mushroom and Spinach

b. Taco Pizza

2. The crust of the pizza is usually soft and tasty.

B. Vegetarian Food

C. Falafel

D. Couscous

E. Stuffed Portobello Mushrooms

F. Cereal

G. Ten different kinds are always available

H. Saga is continually rotating the selection.

II. Saga’s atmosphere is conducive to students’ social needs.

Common organizing principles include:

- Chronology (useful for historical discussions – e.g., how the Mexican War developed)

- Cause and Effect (e.g., what consequences a scientific discovery will have)

- Process (e.g., how a politician got elected)

- Logic (deductive or inductive)

A deductive line of argument moves from the general to the specific (e.g., from the problem of violence in the United States to violence involving handguns), and an inductive one moves from the specific to the general (e.g., from violence involving handguns to the problem of violence in the United States) (MLA Handbook 32).

Internet Resources:

>> OWL Purdue Invention Guid e >>

>> OWL Purdue Outlining Guid e >>

>> UNC Understanding Assignments Guide e >>

>> UNC Reading to Write Guide

Copyright © 2009 Wheaton College Writing Center