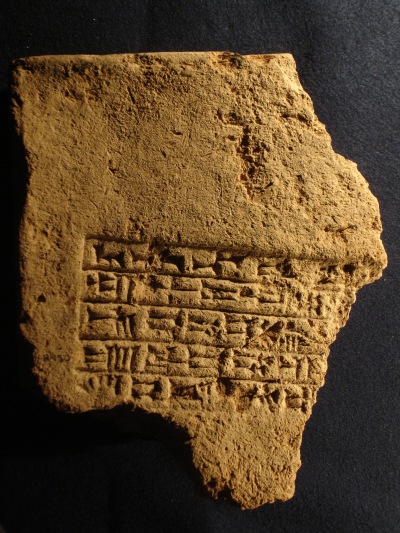

Sargon II Brick

This is a stamped mud-brick bearing the name of Sargon II (721-705), king of Assyria. It reads:

- Line 1: Sargon, king of the universe,

- Line 2: built this city– Dur Sharru-kin

- Line 3: is its name. This unrivalled

- Line 4: palace he had built

- Line 5: within it.

Historically, Sargon II is most famous for extending the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the Arabian Gulf to the Mediterranean.1 In his conquests he came into contact with the biblical world via his campaigns against the Northern Kingdom of Israel, probably assisting his predecessor, Shalmaneser V, with sacking Samaria, the capital of the Northern Kingdom, in 722 BC (Isaiah 20:1). He also captured Babylon in 720 BC, expelling Marduk-apal-iddina (Merodach-Baladan of 2 Kings 20:12 and Isaiah 39:1).2

This particular mud-brick comes from Dur-Shurrukin (‘Fort Sargon’), near modern Khorsabad, Iraq, just 15 miles from Nineveh.3 Sargon lived in Nimrud (Kalhu), but upon his inauguration he commenced the building of a new capital at Dur-Shurrukin. Why he decided to move the capital is unknown, but it is perhaps because of rivalries with the old and well-established families in Nimrud.4 Unfortunately, shortly after the official inauguration of Dur-Shurrukin, Sargon was killed in battle (705 BC) and the city was eventually abandoned.5

Mud-bricks were the building material of choice in Mesopotamia, though stone foundation blocks (orthostats) and decorated panels were used in temples and palaces. This generally sparing use of stone was primarily out of necessity since stone was a scarce resource in the river plains. Bricks were mostly sun-dried, but baked bricks would be used in temple facades and wealthy private homes. These baked bricks, made quite durable when kiln-fired, were used in the monumental building projects of the Assyrian and Babylonian kings.6 “Some of the most important dating information comes from the use, especially in the courtyards of monumental buildings, of baked bricks stamped with the name of the royal builder.”7

Since the time of Naram-Sin of Akkad (2254-2218 BC), Mesopotamian kings have been inscribing or stamping their names onto at least some of the bricks used in their major constructions. Stamps of baked clay or wood, with the inscription in reverse relief, could be used to quickly stamp hundreds to thousands of bricks. While the stamps would have been visible during construction, after the work was completed the message would have only been visible to the gods.8 The kings, however, “were well aware of the propaganda value of creating a permanent record of their exploits. They were also concerned to remind the watching gods of how they had cared for their shrines and supported their cults...some categories of objects became standard vehicles for commemorative inscriptions.”9 The stamped mud-brick constitutes one of the more numerous forms of those standard vehicles and the “physical monuments... especially [of] Sargon at Khorsabad and Assurbanipal at Nineveh, must undoubtedly be counted among the most successful exercises in propaganda ever attempted.”10

Works Cited

Loud, G. and C.B. Altman, Khorsabad, Part 2: The Citadel and the Town , Oriental Publications 40. University of Chicago Press, 1938.

Oates, David and Joan Oates. Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed. Iraq: British School Of Archaeology In Iraq, 2001.

Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. Baltimore: Pelican Books, 1969.

Walker, C.B.F. Cuneiform Brick Inscriptions in the British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum , Oxford, the City of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, the City of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. (London: BMP, 1981). [Heading to OI to check out if I can get any pictures of this stamp].

Walker, C. B. F. Reading the Past: Cuneiform. London: British Museum, 1987.

1 David Oates and Joan Oates. Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed (Iraq: British School Of Archaeology In Iraq, 2001), 22.

2 Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq (Baltimore: Pelican Books, 1969), 281.

3 Roux, 285.

4 Oates, 22.

5 Roux, 286. Notes on seriousness of unrecovered body of Sargon and “Sin of Sargon” see Oates, 22.

6 C. B. F. Walker. Reading the Past: Cuneiform (London: British Museum, 1987), 30.

7 Oates, 220.

8 Walker, 30.

9 Walker 28.

10 Oates, 196. Walker 30: “Almost every collection of Near Eastern antiquities has at least one stamped brick of Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC) from the great temple tower (zigurratu) at Babylon.” “The King, according to custom and ever alert to to the opportunity of perpetuating his fame as the builder of this city, had engraved upon a goodly number of the bricks inscriptions wherein are mentioned his city, palace or name, the last rarely accompanied by one or more of his many titles” [G. Loud and C.B. Altman, Khorsabad, Part 2: The Citadel and the Town , Oriental Publications 40 (University of Chicago Press, 1938), 14].